Last updated:

‘Antonio Azzopardi, Australia’s first Maltese immigrant: an exploration of his life and sources of information’, Provenance: the Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, issue no. 21, 2023-24. ISSN 1832-2522. Copyright © Charlie Farrugia.

During 2023, I collaborated with the National Archives of Australia (NAA) to find records within Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) for an NAA function and display celebrating the seventy-fifth anniversary of the signing of the immigration agreement between Australia and Malta. The function took place at the Victorian Archives Centre on 6 May 2023 and the exhibition, titled ‘From restricted to assisted. Minn Ristrett ghal Assistit. Maltese migration to Australia’, included records I located relating to Antonio Azzopardi, an early European settler at Port Phillip. Starting with a variety of publicly available resources, I then located a range of public records within the PROV collection that assisted in telling part of Azzopardi’s story, most of which could not be included within the exhibition. This paper combines the public records I located with non-government records and secondary sources to produce a sketch of Azzopardi’s life in Victoria and outline his achievements. Although not the main focus, the article also reveals in passing some of the difficulties that occurred in using some of the publicly available resources, as starting points for this research, and some of the public records, and the extent to which various claims made about Antonio’s life could (and could not) be substantiated.

Introduction

According to the Australian census, in 2021 there were 35,413 people born in Malta and 198,989 people of Maltese descent, including myself, resident in Australia.[1] Although Antonio Azzopardi (1805–1881) was almost certainly not the first to arrive, he was the first Maltese person who willingly migrated to the Australian colonies.[2] During 2023, I undertook to find records about him held by Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) for a National Archives of Australia (NAA) exhibition celebrating Maltese immigration. Initially, I found a number of potential sources scattered across the web: academic articles, online reference tools dedicated to particular areas of interest and fragments of information (including images of uncited or partially cited records at PROV) left on social media by Azzopardi’s descendants.[3] From there I constructed a timeline by locating public records held by PROV, augmented with additional public records and other sources. Time constraints meant that aspects of his story requiring intensive research, or involving leads that subsequently proved fruitless, were excluded. Despite this limitation, sufficient information emerged to tell part of the story of a man whose life and career intertwined with numerous activities related to the early years of colonisation in Victoria.

As will become apparent, there are many potential challenges a researcher can encounter when trying to piece together the details of someone’s life and career through primary sources, such as encountering public records that have been destroyed or not yet transferred to the custody of the archives; trying to track activities that are not documented by government records; interpreting information that has not been consistently recorded within records; the deliberate or accidental misspelling of names; and assessing the accuracy of published biographical portraits or death notices written after someone has passed away.

Arrival and work in Port Phillip

The earliest reference to Antonio Azzopardi I could find in public records held at PROV dates from 1845 and so it is not altogether surprising that many details about his life until then appear to have been drawn from a portrait of him in HM Humphreys’s 1882 book, Men of the time in Australia.[4] Published the year after Antonio’s death, it contains written portraits of approximately 500 ‘leading statesmen and colonists … identified with the early history of Australia’.[5] Humphreys did not disclose how these portraits were written; however, if he compiled Antonio’s solely from information provided by family members, it is effectively a written version of oral history potentially containing factual errors stemming from imperfectly understood or remembered details.

According to Humphreys, Antonio Azzopardi was born in 1802, yet every other source consulted states that he was born in the village of Zetjun on 25 January 1805.[6] Humphreys records that, as a young man, Azzopardi served on a French man-of-war and in the British mercantile marine. The story continues that he arrived at Port Phillip in 1838, possibly as the mate to a Captain Nicholson on the Clonmell, and, ‘struck by the prospects on offer’, decided to make it his home.[7] If Azzopardi arrived in 1838, it would have to have been during the last few months of that year, as he is not listed in the general census of Port Phillip completed on 12 September 1838 by Police Magistrate William Lonsdale.[8] It put Port Phillip’s colonist population at 2,278, 1,066 of whom lived in Melbourne or Williamstown. By 31 December that year, this component of the Port Phillip population had grown to 3,511; a year later, it was 4,950.[9]

Conflicting accounts exist about when Azzopardi arrived in the Port Phillip District, all of which, including Humphreys’s, are not supported by records held at PROV. One uncited account dates his arrival as 1839.[10] His Wikipedia[11] page uses this date, stating that he arrived on the Mary Hay in 1839 and other accounts have repeated this claim,[12] probably sourced from death notices published in at least the Argus and the Age.[13] However, another uncited account claims that he arrived in 1837,[14] and this date has been used by Museums Victoria[15] and an article published in Provenance.[16]

Confirmation of Azzopardi’s arrival from records held at PROV is difficult because all of these possible years of arrival predate the systematic creation of government records for unassisted immigrant arrivals at Port Phillip. The registers of assisted immigrants in the PROV collection commenced during 1839 and he is not listed in these volumes.[17]

If Azzopardi arrived in Melbourne on the Mary Hay in 1839 it could only have been on 15 July 1839, the ship’s first ever visit.[18] The Mary Hay made five more visits; however, these occurred during 1840–41.[19] Two newspaper accounts of the vessel’s 1839 arrival identified five passengers by name, none of whom were Azzopardi, and 19 unnamed steerage passengers.[20] Thus, he may have been a steerage passenger or a crew member. It is difficult to confirm Azzopardi’s arrival as a crew member because the systematic creation of government records about crew in the PROV collection dates from 1852.[21]

The arrival of the Mary Hay in 1839 has been confirmed, but Humphreys’s claim that the Clonmell arrived in 1838 under the command of Captain Nicholson has not. A paddle steamer named Clonmel was supposed to ply the Sydney–Melbourne route;[22] however, it visited Melbourne only once, in December 1840, and was wrecked during its second voyage from Sydney on 2 January 1841, all while under the command of Captain Tollevrey.[23]

Azzopardi’s initial career at Port Phillip also cannot be confirmed from public records. According to Humphreys, Azzopardi, for an undefined ‘short time’ after his arrival, ‘continued his connection with the sea, and occupied the position of Chief Officer on several ships trading between Port Phillip, Sydney and New Zealand’.[24] Humphreys claimed that Azzopardi ‘had many opportunities of making money’; however, the only specific opportunity he noted was as an engineer from 1840 on the steamer Aphrasia, the ‘only boat operating between Melbourne and Geelong at the time’.[25] After another ‘short time’, Azzopardi ‘gave up the sea, and joined the service of Mr. Edward Barnett [sic] Green, at that time the chief mail contractor in the colony’.[26] Humphreys did not define the length of this ‘short time’ either, or specify when the association with Green commenced, stating only that Azzopardi obtained a subcontract from Green for the Geelong mail route in 1846.[27] According to a secondary source, in 1846 Green worked in partnership with the original sole contract holder, William Rutledge, for the delivery of the overland mail between Sydney and Melbourne. This partnership had commenced by 1843 and was dissolved in 1847.[28]

Despite this, it is plausible that Azzopardi’s move into mail delivery stemmed from, and continued because of, his association with the Aphrasia. This vessel commenced delivering mail to Geelong in November 1840.[29] It was one of two steamers that transported mail between Melbourne and Geelong, the other being the Vesta, which operated on the route from October 1843 to February 1844 and again from 1846.[30] Edward Green, without Rutledge, began operating the overland mail route between Melbourne and Portland via Ballan, Buninyong and other points from 25 May 1844, commencing a branch route to Port Fairy from 29 July 1844 (the latter was apparently subcontracted to Rutledge[31]). By the start of 1847, Green began operating a second mail route to Portland, this time via Geelong, in which the leg between Melbourne and Geelong was via the daily steamer service,[32] meaning the Aphrasia and Vesta. This suggests that Azzopardi’s subcontract for the Geelong mail, as claimed by Humphreys, was effectively for its transport across Port Phillip Bay.[33] A notice in the Victorian Government Gazette by Chief Postmaster Henry D Kemp dated 28 November 1846 established that, by the time Azzopardi received his subcontract, the departures of both vessels from Melbourne were synchronised with the arrival of the Green/Rutledge contracted overland mail from Sydney.[34] If Azzopardi maintained his connection to the Aphrasia, it can be argued that this activity contradicts Humphreys’s account, but not if Humphreys’s statement that Azzopardi gave up the sea did not include travel across the bay.

To date, Azzopardi’s whereabouts have not been confirmed from public records until at least 1845. He is not listed in any of the returns completed during the 1841 census of New South Wales, for which photocopies of households recorded in the Port Phillip District are held at PROV.[35] He also does not appear in the 1843–44 valuation book for the Town of Melbourne as either an owner or occupier.[36]

Properties and business interests

Antiono Azzopardi’s public record trail begins with two, probably interrelated, developments that occurred roughly within the same year. One was his marriage to a Scottish woman, Margaret Sandeman, on 23 October 1845 at the Collins Street Independent Congregational Church.[37] Five children followed: three sons, Angelo (1846–1896), Valetta (1851–1943) and Galileo (1856–1930), and two daughters, Claudina (1848–1942) and Theresa (1852–1853).[38]

The second development was that Antonio leased, then purchased, a property with strong ties to the receipt and dispatch of mail. He appears for the first time in the 1845 Town of Melbourne rate book for Gipps Ward as the owner of two properties located in Court No. 1 off Bourke Lane.[39] The first is described as a wooden house of two rooms and the other a brick house of four rooms with a ‘stable yard, &c’. Azzopardi seems to have purchased the latter house as a result of his connection to Edward Green, probably when the Green was establishing a business presence in Melbourne.[40] According to Alfred S Kenyon, Azzopardi was renting a cottage on a half-acre site behind the post office and he:

gave Mr Green a room which served as an office, and a shed in the yard was converted into a four-stall stable. Mr Green occupied these premises for a few months after which, in evidence of his regards for Mr Azzopardi, he bought the property for 90 pounds for him, the amount to be repaid at his convenience.[41]

It is clear from both Kenyon’s account and the 1845 and subsequent rate books that the cottage (Kenyon) or cottages (rate books) were situated on a lane that ran behind an allotment that was the site of the Melbourne General Post Office (GPO). According to Humphreys, Azzopardi:

acquired the property in Post Office-place, with which his name was associated for many years, and a cottage which in the early days, before any post office was built, the mail bags used to be kept until the settlers for many miles around Melbourne came in to sort their own letters.[42]

Humphreys’s identification of the lane as ‘Post Office-place’ is not supported by the rate books, which did not refer to this street name at the time Azzopardi bought it.[43] It is also clear that the cottage was no longer used for mail sorting when Azzopardi purchased it because the first post office on the GPO site was constructed in 1841.[44]

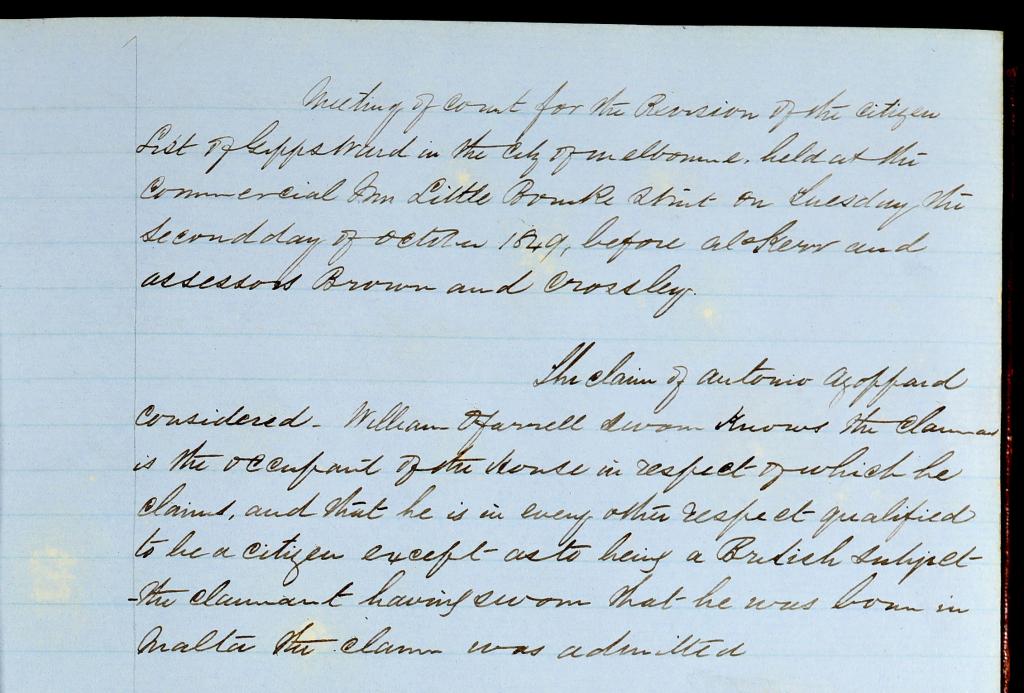

The first of these rate book entries introduced two quirks that create challenges for researchers. One of these, also apparent in many other records consulted, is the apparent misspelling of Azzopardi’s surname as Azzopard (or Azzoppard), which may or may not have been deliberate.[45] If deliberate, it is possible that dropping the ‘i’ from Azzopardi may have been done in an attempt to avoid identification or characterisation as a foreigner. Later, in 1849, town officials thought Azzopardi was an alien and ineligible to vote.[46] Azzopardi successfully appealed this decision in the Revision Court by swearing that he was born in Malta (see Figure 1).[47]

Figure 1: Excerpt from the minutes of the Revision Court hearing of 8 October 1849, PROV, VPRS 4039/P0, Minutes of Special Committee, Minutes Revision Court, 1848–1886.

The other challenge in using rate books is the lack of consistency in the descriptions and locations of the Azzopard[i][48] property or properties. In the 1847–48 rate book, a single property is attributed to Azzopard[i], described as a seven-room house and stable located in Court No. 23 on the south side of Little Bourke Street, implying that the two entries in the previous rate book were now regarded as a single residence.[49] The 1849–50 rate book offered a description of a six-room house and shed at Court No. 31.[50] The 1851 book retained this description but listed it at Court No. 36.[51] A review of Azzopardi’s neighbours in these rate books indicates that the property did not, in fact move; it remained in the same physical location. Instead, the description of rateable properties and numbering of areas off Little Bourke Street as ‘courts’ were seemingly made at the discretion of the rate valuer or collector.

‘Garryowen’, in his famed 1888 publication The chronicles of early Melbourne 1835 to 1852, described the lane as ‘a thoroughfare which, although half-flagged, is certainly not the wholesomest in the inter-street communications of Melbourne’.[52] While attempting to dig a cesspool at his property there on 20 November 1848, Azzopardi was assaulted by Patrick and Bridget Keogh who wanted to prevent it. On 18 December, they were tried on five charges in the Supreme Court and found guilty of common assault.[53] Azzopardi signed two depositions about the matter that can be found on the criminal trial brief for the case.[54]

According to Humphreys, Azzopardi’s mail career continued until 1851, when ‘he brought the first gold from Ballarat to Melbourne through Geelong’, after which he ‘started as carrier to the goldfields, at which business he was very successful’.[55] Attempts to find evidence at PROV of Azzopardi’s activities as a carrier of gold have been unsuccessful. Nevertheless, he continued to live in the lane behind the post office and the rate books bear out Humphreys’s statement about his success. All reference to the courts off Little Bourke Street were removed from the 1853 rate book. The location of Azzopard[i]’s property was given as ‘Little Bourke St. South Side’, most likely the back of a property at 8 or 10 Little Bourke Street.[56] There are broadly similar entries in the next three rate books, with the address given as ‘off Little Bourke Street’.[57] He was listed as the owner of a second property in the 1854 rate book—a brick house with two rooms and an attic, also located off Little Bourke Street but on its north side.[58] However, it appears that he sold this property within the year because he is not listed as its owner in the succeeding rate book.

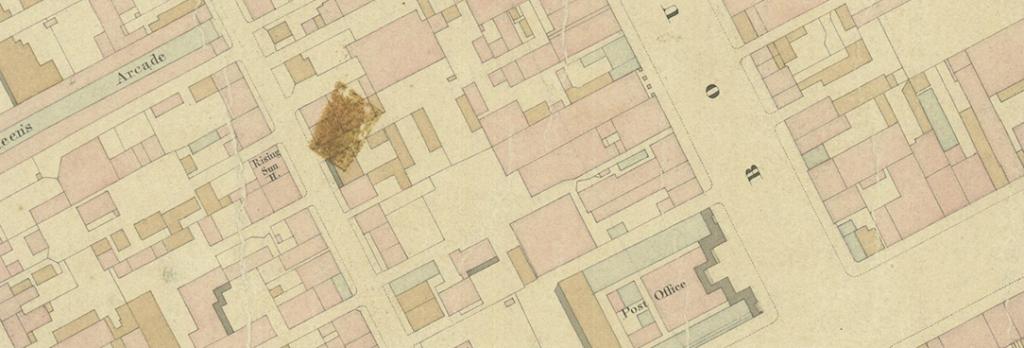

A visual representation of where Azzopardi lived up to this point is documented in a plan held at PROV (Figure 2). The plan was most likely prepared in late 1856. It is one of two plans commonly referred to as the ‘Bibbs map’.[59] It appears to show the two houses in the area behind three properties fronting onto Little Bourke Street.

Figure 2: Redacted excerpt from the ‘Bibbs map’, c. 1856, PROV, VPRS 8168/P3 Historic Plan Collection, item MELBRL12. Azzopardi owned the two pink coloured structures behind the police office (located within black rectangle). The white colouring alongside one of these might be the stables. He would eventually own all three of the structures to the left of these buildings fronting Little Bourke Street. The lane running between Bourke and Little Bourke streets (shaded in light red), from which the houses could be accessed, can also be made out.

The 1857 rate book does not identify any properties owned by Azzopardi in the inner-city area because he moved to bayside St Kilda.[60] He is listed in the 1857–58 St Kilda rate book as the owner and occupier of a plot of land with a 41-foot frontage on the corner of Princess and Burnett streets and a wooden six-room house plus stable next door in Burnett Street,[61] a short distance from Edward Green’s mansion, ‘Barham’, in Grey Street.[62] He presumably sold both properties as he is not listed at these locations in the next rate book for the years 1859–61.[63]

While in St Kilda, Azzopardi’s name was brought up during police enquiries into the whereabouts of another Maltese man, Giuseppe (or Joseph) Azzopardi (no relation).[64] These enquiries led authorities to Castlemaine. In a letter dated 21 December 1857, Superintendent CH Nicolson reported to the chief commissioner of police that, while it could not be ascertained whether Giuseppe ever lived in or near Castlemaine, a person identified as Antonio Azzopardi was ‘maybe identical with him’. The report stated that Antonio worked as a wine merchant in Melbourne, had arrived in the colony about 14 years previously and had been at Forest Creek in 1852.[65] The report also included a physical description: ‘Antonio Azzopardi about 45 years old, middle height, square muscular frame, large head and face, grey cushy hair, heavy eyebrows, sallow complexion, foreign accent, says he is a Maltese.’[66]

While Antonio’s presence in Castlemaine could possibly be explained by his carrier work to the goldfields, some of the details in the report were definitely inaccurate and others might be inaccurate. As it turned out, Giuseppe Azzopardi was in Castlemaine at this time, which suggests that the physical description was of him and not Antonio.[67]

Pinning down Antonio Azzopardi’s home address for the years 1859 to at least 1862 is difficult and requires more detailed research. He is recorded in the Gipps Ward rate book for 1860 as the owner of a brick building in Little Bourke Street—in the same ‘off’ Little Bourke Street area he had seemingly vacated.[68] In the next rate book held by PROV, 1862, he is recorded as the owner of the adjoining property, another brick building, owned by the firm Abbott & Co.[69] This proved to be the tip of the iceberg. The 1863 rate book revealed ‘Antoneo Ezzopard’ to be the owner of no less than seven adjoining properties, being:

- several wooden buildings used as a carpenter’s workshop occupied by George Barber in Angelo Lane off Little Bourke Street

- two wooden houses of three rooms each occupied by ‘Antoneo Ezzopard’ in Angelo Lane

- a ‘wooden shop occupied for coffee roasting’ occupied by Benjamin Blomfield at 14 Little Bourke Street

- a brick shop and tin warehouse occupied by RJ Harworth at 12 Little Bourke Street

- a wood and brick printing office occupied by Abbott & Co at 10 Little Bourke Street.[70]

In all probability, the three properties on Little Bourke Street (i.e., the properties occupied by Blomfield, Harworth and Abbott & Co) are those shown on the 1856 ‘Bibbs map’.

These entries are notable for providing a name to the ‘off–Little Bourke Street’ area. Angelo Lane was first applied to this passage in the 1860 rate book.[71] It formed the eastern boundary of a strip of land marked on its western boundary by a right of way that ran behind the Melbourne GPO. At times, the lane was also known as Angel Lane.[72] Any traces of the lane, including the buildings on it, were demolished during 2009 when the area was absorbed into the redeveloped Myer building.[73]

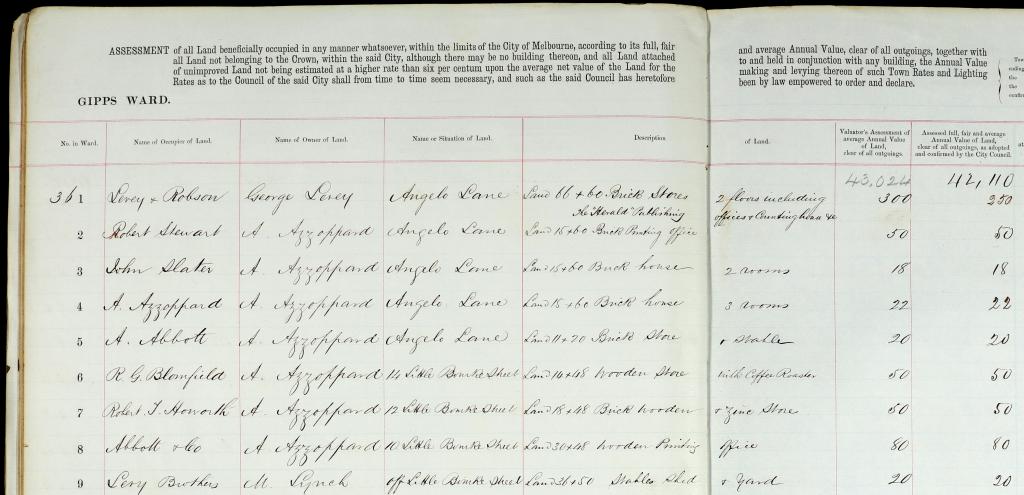

Azzopardi’s presence in the area expanded to seven properties in the 1864 rate book, with a property occupied by Robert Stewart marking another connection to the printing industry. But it was another addition to the Angelo Lane entries in this rate book—one not owned by Azzopardi—that was arguably more significant. This was a property seemingly next door to, or possibly in the same building as, the Stewart printing office (the rate book entries are difficult to interpret), owned by George Levey and occupied by ‘Levey & Robson’. It was described as ‘brick stores 2 floors including the “Herald” Publishing Office and counting house etc’. The Herald’s presence in this building on the corner of Bourke Street/Angelo Lane meant, for a time, that the lane was known as Herald Passage, although this was never incorporated into the rate books.[74] George Levey had probably established the Herald office in the Bourke Street/Angelo Lane building after becoming its editor and proprietor in 1863, positions he held until 1868.[75] Figure 3 shows Antonio Azzoppard[i]’s property portfolio, with buildings in Angelo Lane and around the corner in Little Bourke Street.

Figure 3: Excerpt from the 1864 rate book, PROV, VPRS 5705/P0, Rate Books (Gipps Ward).

There is little doubt that the Levey family became a major influence on the Azzopardi family. George’s brother Oliver Levey, who was a co-owner of the Herald along with George and their brother William,[76] was to eventually work in partnership with Antonio’s son Angelo for a short time,[77] ultimately becoming the executor of Antonio’s estate. More importantly, it has been claimed Antonio started to work for the Herald as a canvasser.[78]

The 1864 rate book marked the start of a 15-year period in which a number of printing offices were located in Angelo Lane or around the corner in Little Bourke Street, some of which were seemingly owned by Antonio Azzopardi.[79]

The Angelo Lane printing office occupied by Robert Stewart in 1864 was taken over by AL Henriques, who maintained occupancy from 1866 to 1870, and then RP Hurren from 1871 to 1873. RM Abbott occupied the store and stable identified in the 1864 rate book until 1870. The remaining two properties were the houses occupied in 1864 by John Slater and Antonio himself. Henriques occupied the Slater house next door to his printing office between 1866 and 1867. Antonio occupied the other house during this period, and both houses between 1868 and 1870. He had vacated the Slater/Henriques house by 1871, which was then occupied by the printing firm Markby & Co. until 1874. ‘A Azzopardi’ occupied the other house until 1873, when the occupier was given as ‘Azzopardi & Co.’, replaced the following year by Markby & Co. In 1875, both houses were occupied by the ‘Govt Post Office’, after which all references to these houses ceased.[80]

The rate books show that Antonio Azzopardi owned two further properties occupied by printing offices on, and around the corner from, Angelo Lane in Little Bourke Street. One of these was the Abbott & Co. printing office, which was given the physical address of 10 or 12 Little Bourke Street or simply ‘Little Bourke Street’ up to 1872.[81] The other printing office was next door; it was recorded as being at 12 or 14 Little Bourke Street or just ‘Little Bourke Street’. Between 1864 and 1872, this property was described as a forge and store occupied by Harworth (1864), Azzopard & Co. (1866) and George Robertson (1867–72). Between 1873 and 1879, the occupier of both printing offices was listed as ‘Azzopardi & Co.’, with the exception of 1874, when both were occupied by ‘Azzopardi, Hildreth and Coy.’[82]

These developments during 1864–79 point to changes in Azzopardi’s career despite a lack of clarity in the rate book entries regarding the occupants in the properties he owned. The rate books make it clear that, for most of this period, Azzopard[i] occupied only one of these properties. However, the names of businesses recorded as occupying the properties in which Antonio didn’t reside do not always correlate with the names of businesses recorded in other sources. Specifically, ‘Azzopardi and Co.’ was used on a number of occasions in rate books, yet I was unable to find any evidence of a business with that name.

This is significant because several of the sources I consulted stated or implied that Antonio Azzopardi bought a printing press; however, it was not clear whether he purchased an entire business or merely the property such a business occupied. For example, an online biography for Angelo Azzopardi states that he purchased RM Abbott’s printing works;[83] however, the rate book entries show that Abbott & Co. occupied the site for a number of years until 1873, when the occupier was identified as Azzopardi and Co. Another online resource identifies a business by the name of Markby & Azzopardi located in Herald Passage in 1872, when the rate book entry identifies the occupier as Markby & Co.[84] Further, as already noted, the 1873 rate book refers to the printing offices of Azzopardi, Hildreth and Co. printing offices.

The Sands & McDougall directories provide a degree of evidence regarding business names and addresses; however, the exact nature of Antonio’s involvement in these businesses is better established with reference to government records. The registration of printing presses in Port Phillip/Victoria was governed by New South Wales legislation until the passage of the Victorian Printers and Newspaper Registration Statute 1864 and subsequent legislation known as the Printers and Newspapers Act. The statute required ‘every person who has any printing press or types for printing’ to be registered by the registrar-general.[85] A witnessed notice in writing had to be lodged with the registrar-general, who, in turn, was required to file the notices and provide the applicant with a certificate. The Act was repealed in 1998.[86] To date, no series relating to this function of the Office of the Registrar-General has been transferred to PROV.

Fortunately, in 1997, Thomas Darragh published a book entitled Printer and newspaper registration in Victoria, 1838–1924 that contains transcriptions of key details, including registration numbers, for the documents lodged during those years and held by the registrar-general at the time of publication.[87] These transcriptions, in conjunction with the rate books and Sands & McDougall directories, clarify matters.

It appears that Antonio Azzopardi only owned the building occupied by the printer RM Abbott—he did not own or operate the printing office himself. According to Darragh, the letterhead to a printing notice submitted by John Lewis on 2 August 1872 states that he was the ‘Successor to R.M. Abbott & Co’.[88] The address of Lewis’s steam printing works was given as the ‘Late Advocate Office’ at 7 Post Office Place[89]—that is, across the street from the Azzopard[i]–owned properties on the south side of Little Bourke Street East/Post Office Place. This indicates that Lewis had relocated the business.[90]

Darragh’s transcriptions further reveal that Antonio Azzopardi owned the buildings occupied by a printing business operated by others. On 18 February 1876, a notice was filed by John Markby and Angelo James Azzopardi stating they held a printing press in Elizabeth Street.[91] This marked the culmination of an association that seems to have begun in Angelo Lane. The 1871 rate book indicates that ‘Markby & Co.’ and ‘A. Azzopardi’ each occupied one of the two houses owned by Antonio in Angelo Lane/Herald Passage. The 1871 Sands & McDougall Directory reveals that Markby & Co. was a label printing business, and the house next door was occupied by Angelo J Azzopardi, an ‘engraver and draughtsmen on wood’.[92] The 1872 directory refers to a business called ‘Markby & Azzopardi’ in Herald Passage, and, although it was not identified in either the 1874 or 1875 directories, it appears that the business remained in Angelo Lane/Herald Passage until at least 1874, according to the rate books, albeit identified as ‘Markby & Coy’.[93]

It is clear that the ‘A Azzopardi’ identified in the rate books as occupying one of the houses in Angelo Lane/Herald Passage between 1871 and 1874 was Antonio’s son Angelo. Unlike his father, Angelo, it seems, had no qualms about placing the ‘i’ at the end of his surname. Nor did his brother Valetta, one of three principals in the printing firm of Azzopardi, Hildreth and Co. Formed by Antonio and Valetta Azzopardi and Joseph Hildreth, the company filed a joint printing notice on 17 March 1873 stating that they had a press or presses located at 10, 12 and 14 Post Office Place. The business was located at the same address in the Sands & McDougall Directory for the years 1873–79, identified as ‘Azzopardi VS and Hildreth printers’ in the final of these.[94] No reference to this business appears in the 1880 directory or rate book.

Indeed, by 1880, Antonio owned only one property in the area, marking the completion of either the sale or consolidation of his City of Melbourne properties into a single rateable property. On the surface, the sole property remaining in 1880 was the only one not associated with printing. Previously the shop/coffee roaster business occupied by Blomfield, the address of this property was given in some of the rate books between 1864 and 1878 as 16 Little Bourke Street, an address backed up by the directories. Blomfield’s occupancy ceased prior to the compilation of the 1879 rate book, the entry for which contained the description ‘brick building in course or erection’ alongside the two properties occupied by ‘Azzopardi and Co.’ (in reality, Azzopardi, Hildreth and Co.) at 10–14 Little Bourke Street.

The notice of intention to build, submitted to the City of Melbourne building surveyor by the builders Martin and Peacock on 28 November 1878, stated that the building was to be a printing office.[95] However, the 1880 rate book entry for this property, owned by Antonio, described it as a brick store located at 14 Post Office Place. Significantly, the occupier was identified as the ‘G[eneral] Post Office’.

This was probably inevitable. After the construction of the main GPO building during the 1860s, the post office had begun to encroach on the strip of land on which Angelo Lane and the Azzopardi properties were located. The land fronting Little Bourke Street from Elizabeth Street that extended to the Azzopardi-owned properties at 10–16 Little Bourke Street/Post Office Place was part of the original allotment reserved for government buildings. The ‘Bibbs map’ shows that a police office had been erected on that site and that the post office intended to build the north-wing of the GPO building there.[96] In 1872, it constructed a wood and iron ‘temporary’ telegraph office that was replaced in 1907 by another ‘temporary’ telegraph office that came to be known as the ‘Old Tin Shed’.[97] The post office was identified as the occupier of Antonio Azzopardi’s two Angelo Lane houses in the 1875 rate book; the government probably purchased the properties from him after that. In late 1879, it was reported that the government had secured a ‘splendid site’ extending from the footway ‘right up to Mr Azzopardi’s new building in Little Bourke Street’, which was to be the site for a new electric telegraph office.[98]

Retirement and legacy

By the time the post office acquired Antonio Azzopardi’s city properties, he had retired. The rate books indicate that he had moved from Angelo Lane by 1871. He next appears in the East Collingwood/Collingwood rate books created between 1872 and 1875 as the occupier of a brick house situated in Victoria Street/Parade, near Mason Street.[99] In 1876 he moved again, being recorded as the owner and occupier of a two-storey brick house located at 5 Erin Street, Richmond.[100] It seems this was his final move, as the rate book entry for 1877 recorded his occupation as ‘Gent[leman]’, replacing the previous year’s designation as printer.[101]

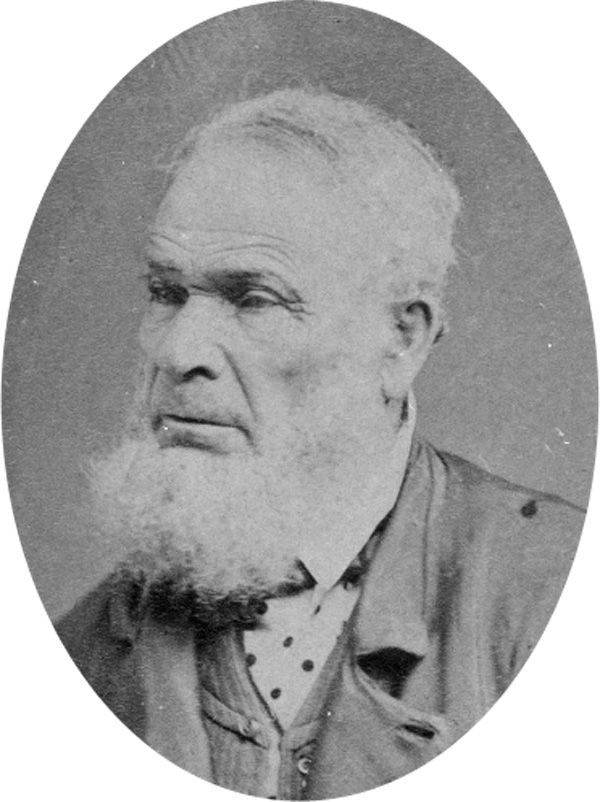

By then Azzopardi was recognised as one of the earliest European settlers of Victoria. Humphreys claimed that he was one of the first members of the Old Colonists Association.[102] Although he was not reported as being in attendance at the preliminary gathering that established the association in May 1869,[103] he was admitted as a member at one of its first official meetings two months later.[104] In 1872 his image was included in a photographic montage published by Charles Foster Chuck entitled The explorers and early colonists of Victoria (see Figure 4).[105] The montage incorporated images of 713 individuals, each numbered seemingly in rough chronological order by arrival: Antonio was number 84. A key (i.e., index) to the montage was also published that identified each individual and their year of arrival. Antonio’s surname was accurately rendered as ‘Azzopardi’ and his year of arrival was recorded as 1839.[106] Since Chuck created the montage by photographing some of the surviving colonists himself, it is possible that he obtained the year of arrival directly from Azzopardi.[107]

Figure 4: Image of Antonio Azzopardi published by Thomas Foster Chuck in The explorers and early colonists of Victoria, 1872.

Antonio Azzopardi died at his home in Richmond on 23 January 1881 and was buried at the Melbourne General Cemetery.[108] In his will, in which he identified himself as Antonio Azzopard, he left most of his estate to his immediate family. He did not nominate an executor but provided for his real estate interests to be managed in accordance with detailed conditions outlined in the will by three individuals nominated as trustees.[109] Two of these individuals renounced probate, leaving Oliver Levey as the sole trustee. Azzopardi’s widow Margaret subsequently lodged a caveat against Levey’s advertised notice to apply for probate as its executor. An order was issued, recorded in the Victorian Law Reports, that ruled Levey was both trustee and executor.[110]

The probate file reveals that, in his final years, Azzopardi had made an arrangement with the Postmaster General’s Department regarding his city property that was far more ambitious than a mere rental agreement. A statement and affidavit prepared by Levey of ‘all and singular real and personal estate’ owned by Azzopardi in his probate file revealed the scale of both the property and his agreement:

ASSETS – Real Estate

Land having a frontage of sixty four feet two inches to Little Bourke Street by a depth of one hundred and thirty four feet seven inches along Angel Lane. Eighteen feet of which frontage is occupied by a substantial three storey brick store, the other building being of a temporary character.

In the occupation of the Post Office Department under lease having about five and a half years to run at the annual rental of one thousand five hundred and fifty pounds with option on the part of the Department to renew the tenancy for a further term of seven years the lessee to have the option during the term of purchasing the property for the sum of twenty thousand pounds also the option of removing the buildings put up by them.[111]

It appears that Azzopardi entered into a substantial mortgage in order to build the store and still had £3,000 to repay at the time of his death.[112] Tellingly, his will was dated 22 December 1879, which would have been around the time of the completion of construction, commencement of the lease and the reported sale of the land between the post office and the store.

An article in the Argus on 16 October 1882 appears to confirm the arrangement. It noted that behind the GPO:

is a block of buildings which extends to another right of way, known as the Herald or Angel Lane. These buildings are used for business purposes, and are owned by private individuals. At the rear, however, and extending between the two lanes to Little Bourke Street, is a strip of land in part owned and in part rented by the Government. On this strip, which is now used for stables and other out offices in connexion with the Posts and Telegraph department it is proposed to erect the new telegraph offices.[113]

Azzopardi’s property was eventually purchased, supposedly for extensions to the post office, at the start of 1889 for the £20,000 specified in his will; however, by that time, it was reportedly valued at £70,000.[114]

The administration of Azzopardi’s estate before this sale was contentious. In 1885, his sons took Oliver Levey, as the sole trustee and executor of the estate, to the Equity Court of the Supreme Court. They claimed that Levey had made decisions regarding the administration of the estate without consulting them and accused him of acting contrary to their interests. They also contended that he had not adopted a satisfactory or definite system or scheme for managing the estate and had charged inappropriate commissions. They sought to have the administration of the estate vested with the Supreme Court. The court ruled that it did not manage estates and that two new trustees be appointed to work with Levey.[115] The large Supreme Court file for this case contains documents lodged by both sides, the judgement, notes of evidence and subsequent action relating to the appointment of additional trustees. The final documents, relating to costs, were added to the file in 1916.[116]

Conclusion

This is probably a far from complete rendering of the life of a significant contributor to the development of a number of activities in the Port Phillip District and colonial Victoria. The research I conducted into Antonio Azzopardi’s life and career brought with it a number of challenges, particularly in regard to finding reliable primary sources that could confirm the time of his arrival in Port Phillip and his activities during the first few years in the colony. While there is an abundance of primary sources available in relation to his later property holdings and business activities, particularly in regard to the properties in the vicinity of the GPO building, some of the details remain unclear and open to interpretation. These and other aspects of Azzopardi’s life will require further exploration and discovery. In the meantime, this paper brings together the information I have been able to locate in the short time frame available to me.

Areas I would like to have researched from records held by PROV or the NAA and considered in greater depth are Humphreys’s claim regarding Azzopardi’s goldfields’ business and transport of gold, the chain of ownership of his properties in the files documenting the conversion of general law to Torrens titles (VPRS 460), other general law property records such as memorial books (VPRS 18873), the contents of the Town/City of Melbourne town clerk’s correspondence files (VPRS 3181), records held by the NAA relating to Azzopardi’s dealings with the Postmaster General’s Department[117] and items sent to other Victorian agencies that might be incorporated in their filing systems. I would also like to investigate the subsequent careers of his children. As is the case for any form of archival research, a great deal of patience, digging, interpreting and assessing will be required. It is possible that some of these additional research areas may yield results, potentially altering some of my conclusions—or they may be dead ends, yielding nothing at all. Hopefully this paper will contribute to our understanding of the life of Antonio Azzopardi—an early colonist in Victoria and pioneer of Maltese immigration to Australia.

Endnotes

[1] Wikipedia, ‘Maltese Australians’, available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maltese_Australians, accessed 21 January 2024.

[2] Wikipedia, ‘Maltese Australians’, claims that the first Maltese arrival was possibly a convict named John Pace in 1790, but he may not have been Maltese. The first certain Maltese arrived as convicts around 1810. The entry for Maltese immigration in James Jupp (ed.), The Australian people, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001, p. 580, notes the arrival of convicts Felice Pace in 1810, and Angelo Farrugia (no relation) and Giuseppe Spiteri in 1811. Additionally, Wikipedia, ‘Talk: Antonio Azzopardi’, available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:Antonio_Azzopardi, accessed 21 January 2024, claims that the first Maltese settler was Charles Jacob, who was described as a ‘Maltese servant’ (probably a bonded servant), employed by Charlotte Duffield, who arrived at Fremantle onboard the barque Eqyptian on 28 December 1831.

[3] Most notably, I came across images from PROV and other sources from a Pinterest account credited to Henry Morgan that appears to track the genealogy stemming from Antonio Azzopardi to which I am greatly indebted.

[4] HM Humphreys, Men of the time in Australia: Victorian series, 2nd ed., M’Carron, Melbourne, 1882, available at https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-13818998/view?partId=nla.obj-14089958#page/n193/mode/1up, accessed 6 March 2023.

[5] Ibid., introductory page.

[6] Ibid., p. clxxix. The only account I could locate that puts Azzopardi’s birth in 1802 is Barry York, ‘“A splendid country?” The Maltese in Melbourne 1838–1938’, Victorian Historical Journal, vol. 60, nos. 2–4, September 1989, p. 3. Even then, York clearly inferred an 1802 birth based on Humphreys portrait.

[7] Humphreys, Men of the time in Australia. That Azzopardi was the mate on the Clonmel has been inferred from Humphreys’s portrait.

[8] PROV, VPRS 4/P0, Box 5, Item 1838/211. This census can be viewed online at PROV, https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/540ADE4D-F7F4-11E9-AE98-9BF746893740?image=1, accessed 21 January 2024. A transcription including all names can be found in Michael Cannon (ed.), Historical records of Victoria. Volume three: the early development of Melbourne, Victorian Government Printing Office, Melbourne, 1984, pp. 432–448.

[9] Cannon (ed.), Historical records of Victoria, p. 432.

[10] Design and Art Australian Online, ‘Angelo Azzopardi’, available at https://www.daao.org.au/bio/angelo-azzopardi/biography/, accessed 6 March 2023. This page was created on 1 January 1992.

[11] Wikipedia, ‘Antonio Azzopardi’, available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_Azzopardi, accessed 6 March 2023. This page was created on 9 June 2011.

[12] For example, Tony De Bolfo, ‘Angelo Azzopardi Carlton’s knight of Malta Australian Football League’, Maltese Newsletter: Journal of Maltese Living Abroad, November 2020, p. 16.

[13] ‘Family notices’, Argus, 24 January 1881, p. 1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5968297; ‘Family notices’, Age, 24 January 1881, p. 1, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article204053037.

[14] MSP: Maltese Media Memory Preservation, ‘The Maltese diaspora’, available at http://www.m3p.com.mt/wiki/The_Maltese_Diaspora, accessed 6 March 2023.

[15] Origins, ‘Immigration history from Malta to Australia’, available at https://origins.museumsvictoria.com.au/countries/malta, accessed 6 March 2023.

[16] Yosanne Vella, ‘The search for Maltese troublemakers and criminals in Australia’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, no. 15, 2016–17.

[17] In hard copy, this series is PROV, VPRS 14. These lists, which have been digitised and indexed, can be searched online at https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/explore-topic/passenger-records-and-immigration/assisted-passenger-lists, accessed 21 January 2024.

[18] Refer to Marten A Syme, Shipping arrivals and departures. Victoria ports, Volume 1, Roebuck Society, 1984–87, p. 246; ‘Port Phillip District’, available at https://www.portphillipdistrict.info/in, accessed 21 January 2024.

[19] The Mary Hay arrived at Melbourne three times between April and July 1840 from Hobart, on 18 December 1841 from London and the following month from Launceston. Syme, Shipping arrivals, p. 246.

[20] ‘Ship news’, Port Phillip Patriot and Melbourne Advertiser, 15 July 1839, p. 3, supplement, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article228129475; ‘Shipping intelligence’, Port Phillip Gazette, 17 July 1839, p. 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article225007233.

[21] Refer to the topic page on the PROV website, ‘Ships’ crew (1852-1922)’, available at https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/explore-topic/transport/ships-crew-1852-1922, accessed 21 January 2024.

[22] It first arrived in Sydney on 2 October 1840, misspelt as the Clonmell. See ‘Arrival of the “Clonmell”’, Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser, 6 October 1840, p. 3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article32185649.

[23] Wikipedia, ‘PS Clonmel’, available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PS_Clonmel, accessed 10 March 2023.

[24] Humphreys, Men of the time in Australia, p. clxxx; York, ‘A splendid country?’, p. 3.

[25] Humphreys, Men of the time in Australia.

[26] According to another source, Green was ‘one of the original contractors for the carriage of mails from Sydney to Melbourne’. See ‘The Greens of “Braham” Station N.S.W’, in Alfred S Kenyon, The story of Australia: its discoverers and founders, Corio Press, Geelong, [1937], pp. 20–21. Note: this book has two sequences, each with its own pagination. The reference is in the second sequence subtitled Founders of Australia and their descendants. Every source I’ve located about Green, apart from Humphreys, states that his name was Edward Bernard Green—not Edward Barnett Green.

[27] Humphreys, Men of the time in Australia.

[28] Richard Breckon, ‘Inland mail routes of the Port Phillip District: an article relating to inland postal routes in the Port Phillip Era, 1838–1851’, Philately In Australia, March 1998, pp. 23–24, https://www.latrobesociety.org.au/documents/InlandMailRoutes.pdf. Breckon’s first reference to Green is through a partnership with William Rutledge for the overland mail from Sydney to Melbourne from 1843, although an alternate reading of his claim could date the partnership from 1840. (Rutledge first obtained the contract by himself in 1839.) In 1843, Rutledge moved to Port Fairy and might have left Green to run their operation from Melbourne, thus explaining Humphreys’s claim of receiving the subcontract just from Green. See Martha Rutledge, ‘Rutledge, William (Billy) (1806–1876)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, available online at https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/rutledge-william-billy-2622/text3625, accessed 21 January 2024.

[29] Report of the Post Office Department, Victoria, to 30th September 1862, p. 6, in Papers Presented to Parliament Session 1862–63, vol. 4.

[30] Ibid.; Breckon, ‘Inland mail routes’, p. 24

[31] Kenyon, The story of Australia, p. 21

[32] Breckon, ‘Inland mail routes’, p. 24.

[33] Breckon, ‘Inland mail routes’, states that an overland parcel, then mail, delivery service, contracted to William Wright, operated between Melbourne and Geelong between June 1839 and September 1841, but authorities didn’t renew the contract because it was too expensive and delivery by sea was thought to be cheaper.

[34] Victorian Government Gazette, no. 47, 6 November 1846, p. 301, https://gazette.slv.vic.gov.au/view.cgi?year=1846&class=general&page_num=301&state=P&classNum=G48&searchCode=6699044.

[35] Refer to PROV, VPRS 85.

[36] PROV, VPRS 3102/P0, Unit 1. A rate book for the Town of Melbourne is not known to exist for this period.

[37] Wikipedia, ‘Antonio Azzopardi’.

[38] Years of birth established at Ancestory.com, family tree available at https://www.ancestry.com.au/genealogy/records/antonio-cajetanus-matthias-azzopardi-24-5bcgfl, viewed 27 March 2023. Using the Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria online searching tool, I could only find birth index entries for Claudina (birth registration 1853/11966), Valetta (1853/11967) and Theresa (1853/11968), all of which are indexed as Azzopard instead of Azzopardi.

[39] See Gipps Ward rate book, PROV, VPRS 5708/P1, Box 1. It appears that Bourke Lane was the previous name for Little Bourke Street, at least according to the rate books.

[40] Kenyon, The story of Australia, pp. 18–19. By the time he met Azzopardi, Green had already purchased a number of allotments within Melbourne, adding to his major holdings of stations in southern New South Wales. He probably required a Melbourne business base, having purchased 640 acres of land in Keelbundoora, which he renamed Greensborough, in 1841. See Wikipedia, ‘Greensborough, Victoria’, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greensborough,_Victoria, accessed 17 April 2023.

[41] Kenyon, The story of Australia, pp. 19–20.

[42] Humphreys, Men of the time in Australia.

[43] Understandably, Humphreys used the street names in place at the time he wrote up his portrait in 1882. This address was not used in the rate books until 1879.

[44] Report of the Post Office Department, Victoria, to 30th September 1862, p. 6. The 1841 post office was replaced by the present-day GPO building during the 1860s. See Wikipedia, ‘General Post Office, Melbourne’, available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Post_Office,_Melbourne, accessed 15 March 2023.

[45] The rate books were not the only records in which his name was spelled this way, which is the basis for my contention that this form of spelling was deliberate. However, the rate books, as will be demonstrated throughout this paper, were unique due to many variations of his surname and even, on one occasion, his Christian name.

[46] ‘Report Revision Court – Gipps Ward’, Argus, 4 October 1849, p. 2.

[47] Minutes Revision Court, PROV, VPRS 4039/P0, Unit 6.

[48] Note: ‘Azzopard[i]’ explicitly refers to entries in the rate books when Antonio’s surname is spelt as either ‘Azzopard’ or ‘Azzoppard’.

[49] PROV, VPRS 5705/P0, Unit 1, Folio 31, no. on rate 361.

[50] PROV, VPRS 5705/P0, Unit 2, Folio 49, no. on rate 481.

[51] PROV, VPRS 5705/P0, Unit 3, Folio 46, no. on rate 544.

[52] ‘Garryowen’ (Edmund Finn), The chronicles of early Melbourne 1835 to 1852: historical, anecdotal and personal, vol. 2, facs. ed., Fergusson and Mitchell, Melbourne, 1888, p. 833. Garryowen refers to the lane as ‘The Herald Passage’—a popular (rather than official) name used to describe it at the time.

[53] ‘Supreme Court (criminal side)’, Port Phillip Gazette and Settler’s Journal, 23 December 1848, p. 3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article223157766.

[54] The Crown case against the Keoghs can be found in criminal trial brief 1-57-3, PROV, VPRS 30/P29, Box 6. An account of the trial is given in ‘Supreme Court (criminal side)’.

[55] Humphreys, Men of the time in Australia.

[56] The entries either side of Azzopard[i]’s in this rate book are for 10 and 8 Little Bourke Street. Combined with the (back) reference, this presumably places the property behind one of these two buildings.

[57] PROV, VPRS 5705/P0, Unit 5, (1854), Folio 17, no. on rate 350; Unit 6 (1855), Folio 20, no. on rate 410; Unit 7 (1856), Folio 21, no. on rate 426. The citizen rolls for the years 1854–55 and 1855–56 both identify the location as a house off Little Bourke Street. See PROV, VPRS 4029/P0, Unit 2 (1854–1855); Unit 3 (1855–1856).

[58] PROV, VPRS 5705/P0, Unit 5, Folio 7, no. on rate 345. The previous entry in the rate book (i.e., for no. on rate 344) is for 15 Little Bourke Street, which is the reason for my placement of this property on the north side.

[59] For a detailed examination of the two plans referred to as the ‘Bibbs map’, refer to Barbara Minchinton, ‘The Bibbs map. Who made it, when and why?’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, no. 18, 2020, available at https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore-collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2020/bibbs-map, accessed 21 January 2024.

[60] Azzopard[i] is not listed in the town’s citizen rolls for 1856 or 1857.

[61] PROV, VPRS 8816/P1, Unit 1, Folio 6, nos on rate 137 and 138.

[62] Green built ‘Barham’ in 1850. It was eventually renamed ‘Eildon’ and is listed on the Victorian Heritage Register. See St Kilda Historical Society, ‘Barnham Eildon (extant) 51 Grey Street’, available at https://stkildahistory.org.au/our-collection/houses/grey-street/item/90-barham-51-grey-street, accessed 17 April 2023.

[63] PROV, VPRS 8816/P1, Unit 2, Folio 8.

[64] For more detail about Giuseppe Azzopardi and the police search for him in 1857, see Richard Pennell, ‘Looking for Azzopardi: a historic and a modern search’, Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria, no. 10, 2011, available at https://prov.vic.gov.au/explore- collection/provenance-journal/provenance-2011/looking-azzopardi, accessed 21 January 2021. Forest Creek was the site of the Mount Alexander gold rush of 1852 and, as Antonio was involved in the transport of gold, it is possible he was in the area. Refer to https://www.goldfieldsguide.com.au/explore-location/114/forest-creek-historic-gold-diggings/.

[65] PROV, VPRS 1189/P0 Inward Registered Correspondence I, VA 475 Chief Secretary’s Department, Box 813, File 1857/B8234.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Pennell, ‘Looking for Azzopardi’. Based on the details in Pennell’s article, Giuseppe was around 37 years old in 1857. Antonio was 52 years old that year, meaning that the police estimate of Antonio’s age of 45 falls, more or less, at the midpoint between the two men!

[68] PROV, VPRS 5705/P0, Unit 11, no. on rate 451. Unfortunately, at this point, the folio numbering of these rate books ceased. One of the more fascinating aspects about the research that I’ve conducted is the seeming disappearance of the two cottages/houses from the rate books from 1857 only for them to reappear, owned by Azzopard[i], by 1862. I cannot come up with any possible explanation for this.

[69] PROV, VPRS 5705/P0, Unit 12, no. on rate 455.

[70] PROV, VPRS 5705/P0, Unit 13, nos on rate 366 (Barber), 367 and 368 (Antoneo Ezzopard), 369 (Bloomfield), 370 (Harworth) and 371 (Abbott & Co.)

[71] PROV, VPRS 5705/P0, Unit 11.

[72] Edwina Byrne, ‘Angelo Lane’, eMelbourne, available at https://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM01688b.htm, accessed 14 April 2023.

[73] Elizabeth Curtain (a descendent of Antonio Azzopardi), ‘2 thoughts on “Myer Emporium’ and “Lonsdale House”’, Melbourne Heritage Action, available at https://melbourneheritageaction.wordpress.com/photo-galleries/myer-emporium-and-lonsdale-house/, accessed 21 January 2024.

[74] For example, ‘Herald’s Passage’ appears in many addresses given in the Sands & McDougall directories of the era, starting from 1867. As noted above, ‘Garryowen’ also used this name.

[75] Wikipedia, ‘George Levey’, available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Levey, accessed 20 March 2023. It appears that the bulk of the text on this page was derived from a portrait of Levey published in Phillip Mennell, The dictionary of Australasian biography (1892). See Wikisource, ‘The Dictionary of Australasian Biography/Levey, George Collins’, available at https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Dictionary_of_Australasian_Biography/Levey,_George_Collins, accessed 20 March 2023. Levey was also the member for Normanby in the Legislative Assembly between 1861 and 1867. In 1851, shortly after arriving in Victoria, George Levey, for a short time, worked as a clerk to the gold receiver. It is conceivable that these duties might have brought him into contact with Antonio Azzopardi at the start of his gold activities.

[76] David Dunstan, ‘Twists and turns: the origins and transformations of Melbourne’s metropolitan press in the nineteenth century’, Victorian Historical Journal, vol. 89, no. 1, June 2018, p. 21.

[77] Design and Art Australian Online, ‘Angelo Azzopardi’. The exact nature of Angelo’s partnership with Oliver Levey is not outlined. York, ‘A splendid country?’, p. 3, states that Angelo established a lithography service in Queen Street in 1871.

[78] Wikipedia, ‘Antonio Azzopardi’, and elsewhere. I’ve yet to locate a source for this claim. Humphreys does not refer to it, as his portrait does not refer to any aspect of Antonio’s career after 1851.

[79] To keep the research manageable during the short time available, I limited my investigations to just the Antonio Azzopardi–owned printing offices in Angelo Lane and around the corner in Little Bourke Street.

[80] City of Melbourne rate books, PROV, VPRS 5708/P0, units 13 (1875) and following.

[81] Identified as ‘Abbott and Co.’ (1864–67) and ‘RM Abbott’ (1868–72). City of Melbourne rate books, PROV, VPRS 5708/P0, various units.

[82] City of Melbourne rate books, PROV, VPRS 5708/P0, Units 18 (1878) and 19 (1879).

[83] Design and Art Australian Online, ‘Angelo Azzopardi’.

[84] Centre for Australian Art, ‘Markby & Azzopardi’, available at https://www.printsandprintmaking.gov.au/artists/5887/, accessed 27 March 2023.

[85] Printers and Newspapers Registration Statute 1864, no. 212, section 4, available at https://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/vic/hist_act/panrs1864495.pdf, accessed 27 March 2023. All of the NSW Acts repealed by this Act are identified in its first schedule.

[86] Printers and Newspapers (Repeal) Act 1998, available at https://www.legislation.vic.gov.au/as-made/acts/printers-and-newspapers-repeal-act-1998, accessed 27 March 2023.

[87] It is possible that a register was created that no longer exists; however, the Acts governing this activity did not contain provisions mandating the creation or publication of such a register.

[88] From transcription of printing registration no. 366, ‘Lewis, John’, in Thomas Darragh, Printer and newspaper registration in Victoria, 1838–1924, Elibank Press, Wellington, 1997, p. 10. Robert Main [i.e., RM] Abbott had previously submitted a notice dated 29 December 1866 for RM Abbott & Co., claiming to have 12 printing presses and three machines at 10 and 12 Little Bourke Street. See transcription of printing registration no. 179, in Darragh, Printer and newspaper, p. 7.

[89] Darragh, Printer and newspaper, p. 10.

[90] The term ‘Late Advocate Office’ refers to the former office of the Catholic newspaper, which moved its office from 7 Post-Office Place (two doors down from Elizabeth Street) to 23 Lonsdale Street at some point during 1872.

[91] From transcription of printing registration no. 366, ‘Markby John and Azzopardi Angelo James’, in Darragh, Printer and newspaper, p.12.

[92] Melbourne History Resources, ‘Sands & McDougall’s Melbourne and suburban directory for 1871’, p. 2, available at https://omeka.cloud.unimelb.edu.au/melbourne-history/items/show/13, accessed 13 April 2023.

[93] Melbourne History Resources, ‘Sands & McDougall’s Melbourne and suburban directory for 1872’ p. 2, available at https://omeka.cloud.unimelb.edu.au/melbourne-history/items/show/14, accessed 13 April 2023.

[94] Melbourne History Resources, ‘Sands & McDougall’s Melbourne and suburban directory for 1879’, p. 7, available at https://omeka.cloud.unimelb.edu.au/melbourne-history/items/show/22, accessed 14 April 2023.

[95] PROV, VPRS 9288/P1 Notices of Intention to Build, Box 13, notice no. 7841.

[96] ‘The new telegraph office’, Argus, 15 July 1872, p. 7, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5864494.

[97] Facebook, ‘Past2Present’, available at https://www.facebook.com/Past2Present1/posts/1100493249979910:0, accessed 14 April 2023. The Old Tin Shed functioned as the temporary telegraph office until 1920, after which it was leased to an automobile parts business before being demolished in 1964.

[98] ‘Melbourne’, Geelong Advertiser, 27 November 1879, p. 3, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article150169750. It is assumed that the ‘footway’ mentioned in this article refers to the lane behind the post office (probably the present day Postal Place) rather than Elizabeth Street.

[99] Town of East Collingwood special rate book, 1872–1873, PROV, VPRS 377/P0, Unit 17, Folio 242, no. on rate 242; 1873, Unit 18, Folio 7; Town of Collingwood rate books 1874, Unit 19, Folio 7, no. on rate 251; 1875, Unit 20, Folio 7, no. on rate 255. The house was not allocated an address number in any of these books.

[100] Town of Richmond rate books, PROV, VPRS 9990/P1, 1876, Unit 25, Folio 10, no. on rate 324; 1877, Unit 26, Folio 10, no. on rate 326; 1878, Unit 27, Folio 10, no. on rate 323; 1879, Unit 28, Folio 11, no. on rate 328; 1880, Unit 29, Folio 11, no. on rate 338; 1881, Unit 30, Folio 11, no. on rate 343. The description of the property as a two-storey brick house comes from an affidavit of Antonio’s personal and real assets within his probate file. See PROV, VPRS 28/P2, Probate and Administration Files, Box 115, Item 21/877.

[101] Town of Richmond rate book 1877, PROV, VPRS 9990/P1, Unit 26, Folio 10, no. on rate 326.

[102] Humphreys, Men of the time in Australia, p. clxxx.

[103] ‘Old Colonists’ Association’, Argus, 12 May 1869, p. 7.

[104] ‘Old colonists’ meeting’, Age, 30 June 1869, p. 3.

[105] Before Felton, ‘Chuck explorers and early colonists of Victoria 1872 {1880} SLV [PH]’, available at https://www.beforefelton.com/chuck-explorers-and-early-colonists-of-victoria-1872-1880-slv-ph/, accessed 13 April 2023. This site also contains a reproduction of the montage. Chuck originally intended to present it to the public library of Victoria. It was bought instead by the Old Colonists’ Association of Victoria, which donated it in 1880.

[106] State Library of Victoria, ‘Key to the historical picture of the explorers and early colonists of Victoria’, available at https://viewer.slv.vic.gov.au/?entity=IE15096177&mode=browse, accessed 13 April 2023.

[107] Information about the montage comes from Wikipedia, The explorers and early colonists of Victoria, available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Explorers_and_Early_Colonists_of_Victoria, accessed 13 April 2023.

[108] Plot no. MGC-IND-Comp-A-No-36S. See, Find A Grave, ‘Melbourne General Cemetery’, available at https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/639484, accessed 13 April 2023.

[109] Will 21/877 Antonio Azzopard, PROV, VPRS 7591/P2, Box 62.

[110] Victorian Law Reports, ‘Azzopard, Antonio, in the will of [1881] VicLawRp 35; (1881) 7 VLR (I) 30 (7 April 1881)’, available at https://www8.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/vic/VicLawRp/1881/35.html, accessed 21 April 2023.

[111] Probate file 21/877 Antonio Azzopard, PROV, VPRS 28/P2, Box 115.

[112] Ibid.

[113] Argus, 16 October 1882, cited in Victoria: Chief Telegraph Office, Melbourne, available at https://telegramsaustralia.com/Forms/Telegraph%20Offices/Victoria/CTO%20Melbourne.html, accessed 21 January 2024.

[114] ‘The town’, Argus, 5 January 1889, p. 29, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article198062658. Online conversion on 19 December 2023 showed that £20,000 in the 1880s is worth A$3.45 million today; £70,000 is worth just over A$12 million.

[115] ‘Law Report’, Argus, 25 August 1885, p. 10; ‘Law Report’, Argus, 26 August 1885, p. 6.

[116] PROV, VPRS 267/P0007 Civil Case Files [VA 2549 Supreme Court of Victoria], Box 657, File 1885/1990 [i.e., case number 1990 for the year 1885], Angelo Azzopardi Galileo Azzopardi Valetta Azzopardi v. Oliver Levey.

[117] Surviving records created by Victoria’s Postmaster General’s Department were accessioned into the archives of the Commonwealth Government resulting from the function transfer of postal services from the colonies upon the creation of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901.

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples