Author: Tara Oldfield

Senior Communications Advisor

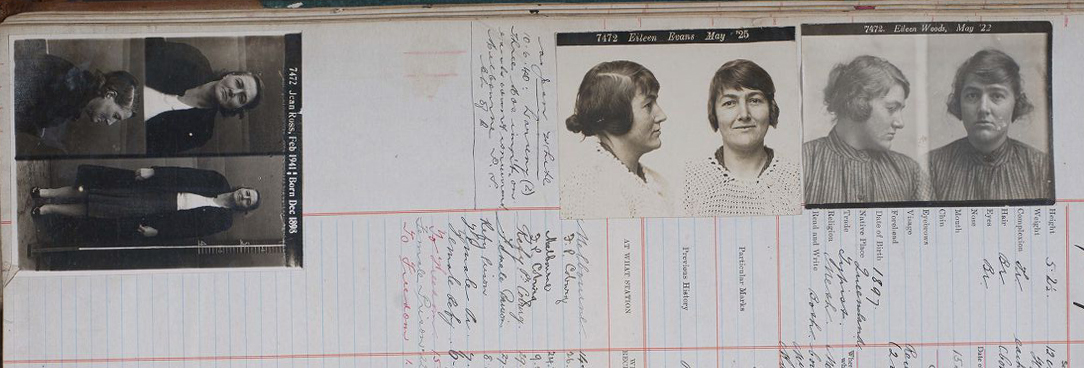

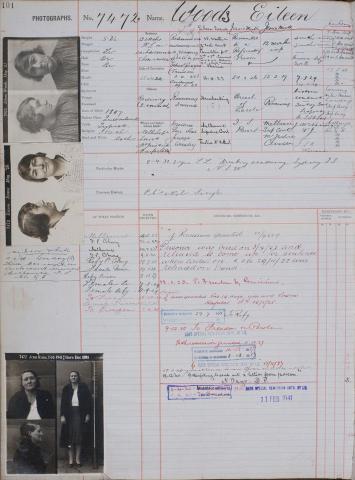

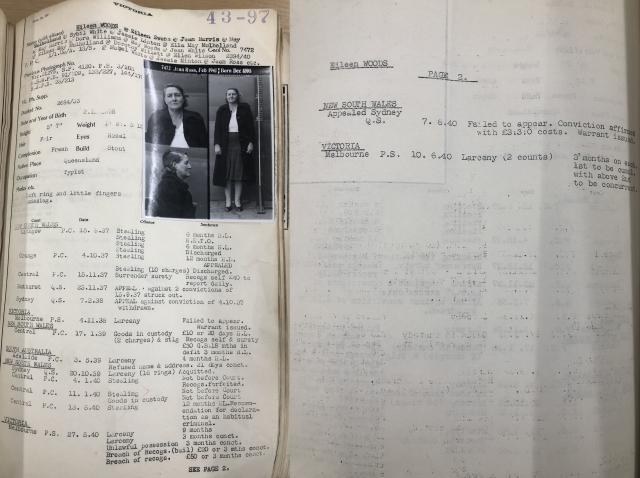

Multiple photographs and listings along the centre of Eileen Woods’ prison register reveals a woman regularly in trouble with the law. Born in 1897 in Queensland, it was in Victoria where she became known as our “most notorious female housebreaker.”

The 1 May 1923 edition of The Age stated:

“The prisoner, a trim and well-developed figure of 25 years, had nobody to speak for her. With her gloved hand resting on the railing of the dock, and with bowed head she awaited the judge’s sentence, looking like one who expected no mercy. She got none. It would be wasted, the judge said.”

Modus operandi

Eileen was a Queensland native, a typist missing her left ring and little fingers, she much preferred thieving to typing. She rarely veered from her tried and trusted routine, finding a house to target where no one was home, then knocking on the neighbour’s door.

“No one’s answering at number 10,” she’d say, or whatever number house she had her eye on. “Do you know if they’re out? How long do you think they’ll be?”

It was amazing how forthcoming these trusting neighbours could be. Eileen would then know just how long she had to break in – usually by smashing the leadlight of the front door so she could put her hand through and let herself in – and ransack the place for all the clothes, coats, jewels and gems she could find.

Throughout 1922 and 1923 she broke into the houses of Thomas Plant, Catherine Grindley, Albert Boast, John Patrick and Marie Antoinette King, David Oswald Nightingale, Doris Rennick, George Frederick Garnham, James Riddell and Maud Evaline Fricke from suburbs such as Camberwell, Balaclava, and Kew. It was a March 1923 break in at James Gaythorn Hackett’s house at Ridgeway Avenue Kew that proved her undoing.

The Hackett theft

She began by knocking on the door of neighbour Mary Veronica Broderick to discover James Hackett and his wife Annie were out for the day. Eileen broke into the home and stole articles of clothing, gold jewellery, war medals, wallet and suitcase. She then visited a confectionary shop nearby for a drink and to use the phone, ringing for a car to pick her up, stolen items in tow. Who did she call? The famous Alice Anderson, who at the time was running the Alice Anderson Motor Service offering everything from vehicle repairs to a 24-hour chauffeur service. In this instance, Alice unknowingly chauffeured a thief.

Alice Elizabeth Foley Anderson:

“I am a Garage proprietor at 88 Cotham Road Kew. On 22nd March about 3.15pm I got a call by phone from 287 High Street Kew to go there with a car for Miss Willaton (an alias adopted by Eileen). I went within 3 minutes. I saw a lady there with a suit case. As far as I can tell I think accused is the person. I am not positive. If she is not the one she is a sister. The suitcase produced is the one she had. She also had a parcel covered with brown paper. She (said) ‘Drive me to Belmont East Melbourne’. On the way she asked me to stop at a Newsagent in Victoria Parade. I did so, and then I took her to Belmont at the corner of Claredon and Grey Streets East Melbourne. I lifted out the suitcase and went to ring the bell for her. She (said) ‘Don’t worry I am meeting someone here.’ She paid me and I left.”

(Sadly, three years later Alice would be dead of a gunshot wound to the head. Her business taken over by her friend Ethel. Learn more about Alice.)

At the Newsagency on route, Eileen (aka Miss Willaton on this trip) asked for the Argus to be delivered to her address at Flat number 7, “Verona” on Gibbs Street East Melbourne.

Upon returning home and finding their house trashed and belongings stolen, the Hacketts contacted the police. Eileen’s movements were easily traced by Constable Michael John James Murphy. He and Constable Penno knocked on the door of her East Melbourne flat, “Hello Eileen we have found you at last.”

They searched her room and found some of the stolen items. Later at the City Watch House they also found a piece of stolen gold jewellery in her handbag.

Gaol time did nothing to dissuade Eileen. After serving two and a half years sentence, a “philanthropic lady” asked the Parole Board to release Eileen under her care and she would provide employment and a good home. Eileen was released on parole 9 December 1925.

“Every assistance was given her both by her guardian and the Board, so that the task of rehabilitation herself would be as easy as possible. In spite of the assistance afforded, she made no attempt whatever to reform, but immediately began a life of crime, grossly deceiving her landlady, the lady who undertook to be responsible for her, and the Indeterminate Sentences Board. This she did very cleverly and thoroughly.” Secretary of the Indeterminate Sentences Board.

She continued committing thefts into the late 1920s, though her MO changed over the years.

Frock loss

In February 1926 Eileen checked into the Oriental Hotel, Collins Street Melbourne, giving her name as Mrs E.J. Miller. After checking in she went straight to the Model Room at Cann’s on Swanston Street and tried on several dresses. She requested they be sent to her hotel room.

Zillah De Wan testified in court:

“I am a saleswoman employed by Cann’s Pty. Ltd., Swanston Street, Melbourne, and reside at 21 Cadman Street, Moreland. On 4th February 1926 Miss Strange, myself and a saleswoman employed at Cann’s were sent to the Oriental Hotel, Collins Street, with three frocks to see a Mrs Miller. We knocked at the door and Mrs Miller, the accused, opened it and said ‘come in’. We went in and showed her the three frocks. This took about five minutes. She said ‘there is one frock you haven’t brought up. I would like to see it.’ Miss Strange went back to Cann’s for it. She returned some time after with the frock. She showed it to the accused, who said ‘I will show it to my sister. She has a room down the passage.’ She went out with the frock leaving us in the room. I did not see her again. We waited for about a ¼ of an hour but she did not return.”

Eileen denied that she was the Mrs Miller accused, she was found not guilty at trial.

Tried on the same day for another case of housebreaking and receiving, she wasn’t so lucky.

Caught red handed

Under the name Jessie Minton she was accused of breaking into the house of Wilhelmina Sleith stealing a case, a bangle, two rings, a brooch, an earring, a choker, six dresses and other articles. She was caught red-handed by Wilhelmina as she returned home. Wilhelmina went straight to the local police who then followed Eileen across Dandenong Road where she went to wait for a tram. On approaching her, Constable Allan Thomas Broderick asked Eileen where she got her suitcase. She admitted she did not own the suitcase and didn’t know who did, before running across High Street. The Constable chased after and arrested her. Still trying to wriggle her way free, on the way to the City Watch House she even tried to bribe the Constable to let her go. He couldn’t be persuaded.

The Indeterminate Sentences Board reported to the Justice:

“She is a very attractive woman, but possesses an inordinate love for finery, which must be satisfied at all cost. She is married, but has been living apart from her husband since about 1920. A son 9 years of age is with friends in West Australia. She states that she has a baby two months old. It is the opinion of prison officials and experienced social workers who know her well that she will never be reclaimed.”

She was found guilty and sentenced to a year in gaol.

Once out, she fled Victoria, was caught stealing throughout NSW and was sentenced to prison multiple times. The late 1930s and early 40s saw her back and forth between Melbourne, Sydney, and Adelaide, committing crimes and doing time in all three cities and racking up a long list of aliases including: Jean Harris, Jean Ross, May Mulholland, Sybil White, Jessie Linton, Ella May, May Harris, Dora Williams, May Woods, Jean White, Eileen May Mulholland, Dorothy Willett, Ellen Wilson, Mabel White, and of course Jessie Minton, and Eileen Evans.

Beyond the 1940s

After a final 1941 stint in gaol in Melbourne it’s unclear whether she finally reformed or simply continued her life of crime without getting caught. As, according to the Indeterminate Sentences Board, Eileen had two children likely in Western Australia staying with friends, perhaps she moved across the country to reunite with her loved ones. But from these records that’s unknown. What we do know is that if and when Victoria’s most notorious female housebreaker went into retirement, it was much to the delight of police and homeowners of Melbourne.

References

- VPRS 30/P0000, 206, 16 Apr 1923

- VPRS 30/P0000, 209, 16 Apr 1923

- VPRS 30/P0000, 207, 16 Apr 1923

- VPRS 30/P0000, 208, 16 Apr 1923

- VPRS 30/P0000, 212, 16 Apr 1923

- VPRS 30/P0000, 140, 15 Feb 1927

- VPRS 30/P0000, 126, 15 Feb 1927

- VPRS 516/P0000, 7412-7780 (1918-1934) Eileen Woods

- VPRS 7856/P0001, 43-97 Eileen Woods

- VPRS 17020/P0001, 3 Apr 1922, 4 Eileen Woods

- The Sun, 24 April 1923, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article223445672

- The Age, 1 May 1923, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article204071537

Material in the Public Record Office Victoria archival collection contains words and descriptions that reflect attitudes and government policies at different times which may be insensitive and upsetting

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples should be aware the collection and website may contain images, voices and names of deceased persons.

PROV provides advice to researchers wishing to access, publish or re-use records about Aboriginal Peoples